Note: the following is a section of Introduction to Quantum-Geometry Dynamics

According to QGD:

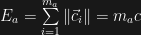

, the mass of an object

, the mass of an object  , is equal to the number of

, is equal to the number of  that compose it;

that compose it; , its energy, is equal to its mass multiplied by the fundamental momentum of the

, its energy, is equal to its mass multiplied by the fundamental momentum of the  ; that is: where

; that is: where  is the momentum vector of a

is the momentum vector of a  and

and  is the fundamental momentum, then

is the fundamental momentum, then  .

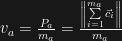

. , the momentum vector of an object, is equal to the vector sum of all the momentum vectors of its component

, the momentum vector of an object, is equal to the vector sum of all the momentum vectors of its component  or

or  and

and , its momentum, is the magnitude of its momentum vector. That is:

, its momentum, is the magnitude of its momentum vector. That is:  and finally

and finally , its speed, is the ratio of its momentum over its mass or

, its speed, is the ratio of its momentum over its mass or  .

.

All the properties above are intrinsic which implies that they are qualitatively and quantitatively independent of the frame of reference against which they are measured. We must however make the essential distinction between the measurement of a property of an object and its actual intrinsic property.

Take for instance the speed of light which we have derived from the fundamental description of the properties of mass and momentum and shown to be constant. That is:  and since, for momentum vectors of photons all point in the same direction we have

and since, for momentum vectors of photons all point in the same direction we have  and

and  .

.

If we were to experimentally measure the speed of light, or more precisely, the speed of photons, we would set up instruments within an agreed upon frame of reference. We would map the space in which the measurement apparatus is set and though the property of speed is intrinsic, thus independent of the frame of reference, the measurement of the property is dependent on the frame of reference. But if, as we know, the speed of light has been observed to be independent of the frame of reference, then how can this be reconciled with QGD’s intrinsic speed?

Before moving forward with the experiment it is important to consider what it is that our apparatus actually measures. Speed is conventionally defined as the ratio of displacement over time, that is  where

where  the distance is and

the distance is and  is time. Space and time here are considered physical dimensions and as a consequence the conventional definition of speed is never questioned.

is time. Space and time here are considered physical dimensions and as a consequence the conventional definition of speed is never questioned.

Distance can be measured by something as primitive as a yard stick and its physicality is hard to argue with. Time and its physicality pose serious problems. Time is assumed to be measurable using a clock of some sort but, it is easily shown that clocks are simply cyclic and periodic systems linked to counting devices and they do not measured time but merely count the number of repetitions of arbitrarily chosen states of these systems.

So conventional speed in general, and that of light in particular, is simply the distance in conventional units something travels divided by the number of cycles a clock goes through during its travel. Therefore the conventional definition of speed, which is the ratio of the distance travelled by an object over the number of cycles, is not the objects speed, but of the distance travelled between two cycles. That goes for the speed of photons.

There is a relation between conventional speed and intrinsic speed and we find that the conventional speed of a photon is proportional to its intrinsic speed, that is  , but while conventional speed is relational (and not physical since time itself is not physical) , the intrinsic speed is physical since it is derived from momentum and mass, both of which are measurable, hence physical.

, but while conventional speed is relational (and not physical since time itself is not physical) , the intrinsic speed is physical since it is derived from momentum and mass, both of which are measurable, hence physical.

Now going back to frames of reference, let us assume a room moving at an intrinsic speed  . A source of photons is placed at the very centre of the room which photons are detected by detectors placed on the walls, floor and ceiling. The source and detectors are linked are in turn linked to a clock by wires of the same length. The clock registers the emission and the reception of the photons in such a way that we can calculate the conventional speed of photons. For now, we will assume that the direction of motion of the room is along the

. A source of photons is placed at the very centre of the room which photons are detected by detectors placed on the walls, floor and ceiling. The source and detectors are linked are in turn linked to a clock by wires of the same length. The clock registers the emission and the reception of the photons in such a way that we can calculate the conventional speed of photons. For now, we will assume that the direction of motion of the room is along the  axis.

axis.

QGD predicts that even though the intrinsic speed of photons is reference frame independent, their one way conventional speed to detector

QGD predicts that even though the intrinsic speed of photons is reference frame independent, their one way conventional speed to detector  will be larger than their one way conventional speed at the detector

will be larger than their one way conventional speed at the detector  . The relativity theory predicts that the conventional speed of photons will be the same at both detectors independently of

. The relativity theory predicts that the conventional speed of photons will be the same at both detectors independently of  . So all that is needed to test which theory gives the correct prediction is to make one way measurements of the conventional speed of photons. Problem is; all measurements of the speed of light are two way measurements and since any possible contribution of

. So all that is needed to test which theory gives the correct prediction is to make one way measurements of the conventional speed of photons. Problem is; all measurements of the speed of light are two way measurements and since any possible contribution of  to the conventional speed of photons traveling in one direction is cancelled out when it is reflected in the other direction. In other words since both QGD and the relativity theory predicts the two way measurements will be equal at

to the conventional speed of photons traveling in one direction is cancelled out when it is reflected in the other direction. In other words since both QGD and the relativity theory predicts the two way measurements will be equal at  and

and  such experiments cannot distinguish between QGD and the relativity theory.

such experiments cannot distinguish between QGD and the relativity theory.

However, a similar experiment which measures not speed but momentum can distinguish between the theories. The photons at detector  will be redshifted while those at

will be redshifted while those at  would be blueshifted. Both theories predict

would be blueshifted. Both theories predict  but their predictions for the other detectors are different.

but their predictions for the other detectors are different.

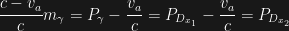

Assuming that the room’s motion is align with the  axis*, the relativity theory predicts that

axis*, the relativity theory predicts that  . For the same experiment the QGD theory predicts

. For the same experiment the QGD theory predicts  .

.

If QGD’s prediction is verified, then the intrinsic of the frame of reference can be calculated using the equations we introduced earlier to describe the redshift effect. That is; from our description of the redshift effect, we know that  then we have

then we have  and

and  .

.

Once the intrinsic speed of a reference system is known, then it can be taken into account when estimating the physical properties of light emitting objects from within it.

QGD’s description of the redshift effect implies distinct predictions for all observations based on redshifts measurement but I would like to bring attention to one direct consequence which has been confirmed by observations; the observed flatness of the orbital speed of stars around their galactic centers .

* The alignment with the  axis is found by rotating that detector assembly so that the

axis is found by rotating that detector assembly so that the  detector measures the lowest momentum (largest redshift).

detector measures the lowest momentum (largest redshift).

which is the fundamental unit of matter.

, being fundamental, do not decay or transmute into other particles but they combine to form all that we know from photons and neutrinos, to more massive and complex structures.

are still free and permeate space and interact in only two ways: Gravitationally and through the electromagnetic effect.

that distributed homogeneously throughout the entire space. The cosmic microwave background was formed when

combined to form photons. Thus QGD explains the isotropy of the CMBR with few physical assumptions; all of them testable using present technology.

account for all other large scale effects attributed to dark matter (gravitational lensing for example) but there are local effects at our scale that we observe or make use of every day.

of their neighbouring regions. And changes in momentum induced by magnetic fields are simply the momentums imparted by their polarized

.

QGD predicts that even though the intrinsic speed of photons is reference frame independent, their one way conventional speed to detector

QGD predicts that even though the intrinsic speed of photons is reference frame independent, their one way conventional speed to detector